On Being Unavailable

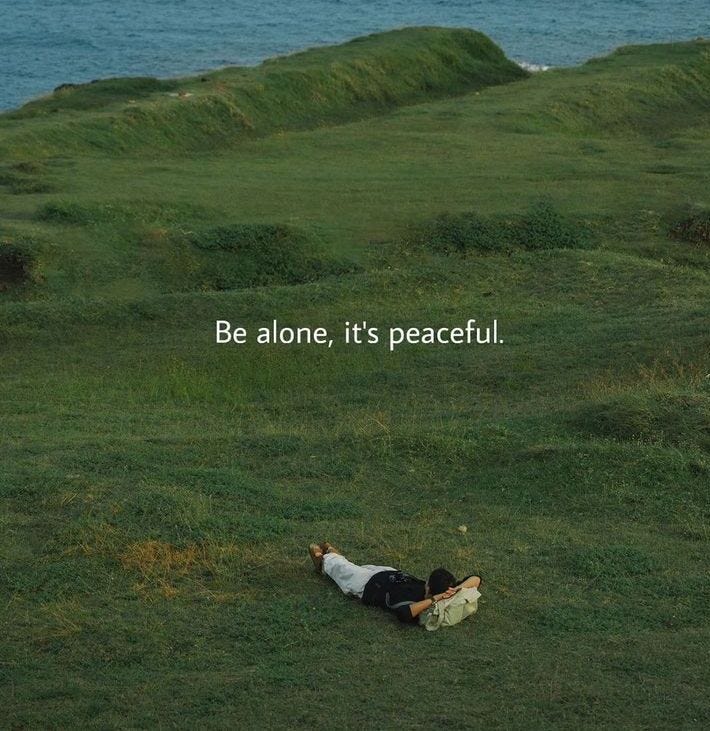

Why phones should be left in drawers and true wealth is to be unavailable.

Not so long ago, and yet now preserved in the amber of memory, there was a time when one could get bored, travel without GPS, do nothing for a few minutes without guilt, and have a meal without the blue glow of a screen illuminating one’s risotto like forensic investigators looking for fingerprints. One could disappear for a few hours or entire afternoons, and no one would find it strange.

Ah, dear reader, what a pleasant feeling that was. Perhaps some of you are not old enough to have known it. A lamentable thing, really. Unavailability is one of the last true luxuries. Not cashmere, not yachts, not caviar flown in from a fishery in the Caspian sea. Not such luxuries, but the pleasant impossibility of being reached.

Phones, those rectangles of anxiety, have usurped every silence, every sunset, every stretch of sun-drenched ennui that once made life bearable. We now live in a collective call centre of our own making, alert to every ping, buzz, and dopamine-dealing notification. I cannot, by any means, find our relationship with these devices remotely healthy. I’ve heard it being referred to as a portable slot-machine, and I found it quite fitting. Gambling is only fun when you don’t bring it with you everywhere you go—even the toilet.

But the truth is that we’ve become allergic to our own solitude. The moment of silence, once the natural state of the thinking person, the flâneur, the afternoon napper, now feels intolerable. God forbid one waits five minutes in line without consulting a glowing oracle to relieve them of their boredom.

Blaise Pascal famously wrote that “all of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” And he said that in the 17th century, when a ‘notification’ was someone physically knocking on your door. Imagine what Pascal would do if handed one of these glowing rectangles. He’d likely hurl it into the nearest river and rapidly take to a chaise longue with a bottle of fortified wine before he’d get contaminated with such filth.

I cannot see this as progress.

The mind, once a garden of slow-growing thoughts and inner monologues narrated by melancholy philosophers, now has been transported to devices resembling casinos: flashing, disorienting, with addictive sounds and designed to keep you from leaving. Even our rest is restless. We scroll as we bathe or eat, and we can’t even watch a film without checking what strangers think of it. And all of this endless presence, this digital servitude, is wrapped in the marketing language of connection. As if being constantly accessible were some modern virtue, rather than a symptom of profound existential insecurity.

Really, is social media even social? I don’t think so

But such, dear reader, is the unfortunate modern human condition.

And so, in this grand opera of modern hyper-connectivity, in which we’re always available, always responding, and always rehearsing our clever replies in the theatre of mutual exhaustion. What exactly are we doing? To whom are we proving our responsiveness? Does our ability to type and chew at the same time matter? We are over-stimulated and under-inspired. It is seems to me not a life of freedom, but of beautifully designed captivity.

Consider this, then, a call to arms.

Or rather, a call to disarm.

I suggest putting your phone in a drawer. Better yet, lock it, place the key in a ceramic bowl, and then place the bowl somewhere inconvenient. Say, behind a pile of unread Virgil leaning on that copy of Dante’s Divine Comedy, you haven’t touched. Let the device be forgotten in its own irrelevance.

Notifications will pile up by the dozens, each one bearing news so urgent, so critical, that they must be ignored immediately for the sake of one’s mental health. Messages, one must fight the urge to reply, lest one triggers yet another text that comes even faster than the previous.

You may think it exaggerated of me, but I believe that being unavailable is to reclaim one’s humanity. It is to suggest, quite impolitely, that not everything is urgent and not everyone is entitled to your attention. Not even this essay is safe, I admit (or perhaps alert?). To availability, I much prefer to sip coffee slowly, to flirt inefficiently, to talk in circles to myself, and to stare at the sea without photographing it.

And so, to the problem of the modern human condition, I offer no app, no hack, no minimalist detox plan. I offer only this modest suggestion: disappear. Not dramatically, but elegantly. Become someone who returns messages three days late, if at all. Leave the house without your phone. Watch the world pass by like an old Italian film.

In the end, no one remembers the messages you sent. But they might remember the way you laughed, or the way you made them laugh, with the sun on your face, a glass of wine in your hands, and your phone in a drawer. Locked, preferably far, far away.

Until next time,

I recently switched to a flip phone... you realize the only thing you really need are texts and calls, everything else can be done on a laptop if you'd like. The mind-silence is soft and wonderful

Important observations for our generations. Thanks for sharing